PIERCY, William Stuckey

Type

Person

7th February 1886 to 7th July 1966

Related Items

Occupation

Biographical Text

Piercy was a businessman and later a stockbroker, who had worked with the Ministry of Munitions during the First World War. He was later a key advisor to Clement Attlee.

Piercy was born on 7 February 1886 in Bermondsey, London, the son of an engineer. He attended school in Hoxton, but left at the age of twelve to become an office boy with the London timber brokerage firm Pharaoh Gane. He continued his education through night school, and from 1912-14 studied economic history at the London School of Economics, where he was also president of the student union.

From 1915-17 Piercy worked with the Ministry of Munitions as a finance officer. From 1917-19 he was in Washington DC as a part of a mission to purchase food supplies, going on to become a director of the Ministry of Food. In 1919 he was awarded the CBE.

Returning to London in 1919, Piercy taught part-time at the London School of Economics and served as marketing director for the East India merchants Harrisons and Crosfield. In 1925 he returned to his old employer, Pharaoh Gane, this time as a director. He worked in the timber trade until 1934 when he went to the city, joining the stock-broking firm Capel-Cure and Terry, where he later become a partner.

In 1941 Piercy became head of the British Petroleum Mission to Washington, tasked with securing the UK’s fuel supplies during wartime. He later became a principal assistant to Clement Attlee, the deputy prime minister, working alongside Evan Durbin. He became a member of the XYZ Group of prominent advisors to Attlee and the Labour Party, including Hugh Gaitskell, Hugh Dalton and Douglas Jay. In 1945, he accepted an invitation from Lord Catto, the governor of the Bank of England and fellow alumnus of the Ministry of Munitions, to become chairman of the Industrial and Commercial Finance Association. Also in 1945 he was ennobled as Baron Piercy for his wartime work.

From 1946-56 Piercy was a governor of the Bank of England. He was also a governor of the London School of Economics and member of the senate of the University of London. From 1954-5 he was president of the Royal Statistical Society, and from 1946-63 president of the National Institute of Industrial Psychology. From 1960-65 he was chairman of the Wellcome Trust, and he had a lifelong interest in charities working with ill or disabled people. He died of a heart attack in Stockholm on 7 July 1966.

Piercy’s lecture on ‘motive in industry’ is interesting because it foreshadows some of the later work on motivation, notably that of Frederick Herzberg in the 1950s. Not a psychologist himself, Piercy nonetheless identifies three elements of motivation: incentive, ‘the inducement to the individual to give his best effort’; the psychological and physiological environment in which the individual works, which affect his or her ability to give of their best (similar to Herzberg’s hygiene factors); and third, ‘the standpoint of management, which must work upon the incentive to the individual within the framework of the most advantageous conditions, in such a way as to produce the best results’. In other words, as Herzberg also identified, management itself can play an important role in motivating – or de-motivating – the worker.

In terms of incentive, Piercy looks at pay and takes issue with the notion that reducing pay makes firms more efficient; in most cases, he says, the opposite happens. But other factors also influence incentive, including prospects of promotion, equity and fairness in terms of discipline and sanction, and ‘positive interest in work’. Several years before the Hawthorne Experiments began, Piercy identified correctly that people will be more motivated to work if they feel their work has meaning and see that work ‘in the context of a business proposition’.

‘The human being is a sensitive, emotional organism’, Piercy says, and he goes on to argue that treating workers with dignity and respect also plays an important role in motivation. He then argues briefly the case for creating workplaces which are safe and allow people to work efficiently, before turning to the question of management. He talks of the relationship between foremen and shop-floor workers and how critical these are, and then assigns to the executive the role of ensuring that those key relationships are smooth and friction less. ‘At bottom’, Piercy concludes, ‘management or administration is, and is likely to remain, an art rather than a science, and success will depend, as largely as anything, on the human quality of every one in authority or control.’

Piercy was born on 7 February 1886 in Bermondsey, London, the son of an engineer. He attended school in Hoxton, but left at the age of twelve to become an office boy with the London timber brokerage firm Pharaoh Gane. He continued his education through night school, and from 1912-14 studied economic history at the London School of Economics, where he was also president of the student union.

From 1915-17 Piercy worked with the Ministry of Munitions as a finance officer. From 1917-19 he was in Washington DC as a part of a mission to purchase food supplies, going on to become a director of the Ministry of Food. In 1919 he was awarded the CBE.

Returning to London in 1919, Piercy taught part-time at the London School of Economics and served as marketing director for the East India merchants Harrisons and Crosfield. In 1925 he returned to his old employer, Pharaoh Gane, this time as a director. He worked in the timber trade until 1934 when he went to the city, joining the stock-broking firm Capel-Cure and Terry, where he later become a partner.

In 1941 Piercy became head of the British Petroleum Mission to Washington, tasked with securing the UK’s fuel supplies during wartime. He later became a principal assistant to Clement Attlee, the deputy prime minister, working alongside Evan Durbin. He became a member of the XYZ Group of prominent advisors to Attlee and the Labour Party, including Hugh Gaitskell, Hugh Dalton and Douglas Jay. In 1945, he accepted an invitation from Lord Catto, the governor of the Bank of England and fellow alumnus of the Ministry of Munitions, to become chairman of the Industrial and Commercial Finance Association. Also in 1945 he was ennobled as Baron Piercy for his wartime work.

From 1946-56 Piercy was a governor of the Bank of England. He was also a governor of the London School of Economics and member of the senate of the University of London. From 1954-5 he was president of the Royal Statistical Society, and from 1946-63 president of the National Institute of Industrial Psychology. From 1960-65 he was chairman of the Wellcome Trust, and he had a lifelong interest in charities working with ill or disabled people. He died of a heart attack in Stockholm on 7 July 1966.

Piercy’s lecture on ‘motive in industry’ is interesting because it foreshadows some of the later work on motivation, notably that of Frederick Herzberg in the 1950s. Not a psychologist himself, Piercy nonetheless identifies three elements of motivation: incentive, ‘the inducement to the individual to give his best effort’; the psychological and physiological environment in which the individual works, which affect his or her ability to give of their best (similar to Herzberg’s hygiene factors); and third, ‘the standpoint of management, which must work upon the incentive to the individual within the framework of the most advantageous conditions, in such a way as to produce the best results’. In other words, as Herzberg also identified, management itself can play an important role in motivating – or de-motivating – the worker.

In terms of incentive, Piercy looks at pay and takes issue with the notion that reducing pay makes firms more efficient; in most cases, he says, the opposite happens. But other factors also influence incentive, including prospects of promotion, equity and fairness in terms of discipline and sanction, and ‘positive interest in work’. Several years before the Hawthorne Experiments began, Piercy identified correctly that people will be more motivated to work if they feel their work has meaning and see that work ‘in the context of a business proposition’.

‘The human being is a sensitive, emotional organism’, Piercy says, and he goes on to argue that treating workers with dignity and respect also plays an important role in motivation. He then argues briefly the case for creating workplaces which are safe and allow people to work efficiently, before turning to the question of management. He talks of the relationship between foremen and shop-floor workers and how critical these are, and then assigns to the executive the role of ensuring that those key relationships are smooth and friction less. ‘At bottom’, Piercy concludes, ‘management or administration is, and is likely to remain, an art rather than a science, and success will depend, as largely as anything, on the human quality of every one in authority or control.’

Bibliography

Obituary notice, The Times, 13 January 1966.

Chick, M., ‘Parker, Richard Barry’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Chick, M., ‘Parker, Richard Barry’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Original Source

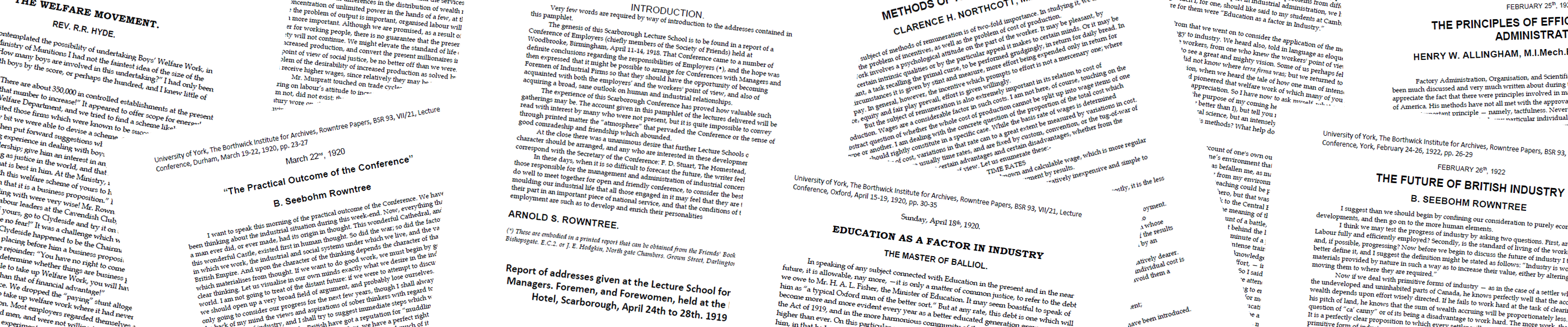

Lecture:

‘Motive in industry’, 21 September 1923, Balliol College

‘Motive in industry’, 21 September 1923, Balliol College

Citation

“PIERCY, William Stuckey,” The Rowntree Business Lectures and the Interwar British Management Movement, accessed July 18, 2025, https://rowntree.exeter.ac.uk/items/show/193.