RENOLD, Charles Garonne

Type

29th October 1883 to 7th September 1967

Lectures

Occupation

Biographical Text

Renold was chairman of Renold Chains and Gears, later Renold plc. He was a leading force arguing for more professional management and more and better management education in inter-war Britain.

Renold was born in Altrincham on 29 October 1883. His father, Hans Renold, a Swiss immigrant, had founded Renold Chains, which became the largest maker of drive chains for bicycles and automobiles. Renold senior was very much interested in improving methods of management, and Urwick (1956: 49) describes him as ‘probably the first British industrialist to appreciate the work of F.W. Taylor and to adapt it to British management practice.’ While Renold did adopt and adapt many of the elements of scientific management, he also tempered this with a more human touch, and wrote and spoke frequently about the need for mutual trust and respect between managers and workers. He was regarded as a model of an enlightened employer; not at all usual for someone who also advocated Taylorism.

Charles Renold was educated at Abbotsholme School and then Cornell University in America, returning to become a director of the firm around 1910, and took over as chairman when Hans Renold retired in 1928. During the First World War he served on the Manchester Armaments Committee, but undertook no further government service. He served for a number of years on the board of the Manchester College of Science and Technology, and was a long-time member of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers. It was mostly through this latter body that he engaged in efforts to promote more and better management education. He also served on the council of the Federation of British Industries.

Renold was knighted KB in 1948. He died at his home in Chapel-en-le-Frith, Derbyshire on 7 September 1967.

Renold’s first Rowntree paper in 1920 on ‘the benefits to the workers of scientific management’ sees Renold working through some of this thoughts on the issue. He begins by asking a question: Does scientific management actually benefit the workers at all? He points out many disadvantages, including repetitive work, the fatigue associated with increased productivity and so on, all of which had already been remarked upon by other observers. Ultimately, Renold comes down in favour of scientific management, but only just. Like many postwar observers of the American industrial scene, he was sceptical of the claims made by proponents of scientific management in the USA, and he was well aware of the dangers inherent in blind application of the principles of Taylorism.

His second paper in 1925 is a fascinating examination of an experiment in industrial democracy and how it had unfolded. Unusually for a Rowntree lecturer, Renold used his own family firm as a case study. Like many progressive companies at time, Hans Renold had a series of employee committees which were consulted on a wide range of affairs, mostly to do with worker welfare. Over time, these had evolved into a broader consultative body, the Works Committee. When management began consulting with the Works Committee on matters of business policy, however, it was discovered that most of the workers had no idea about the wider business picture or business environment.

The result was a series of lectures and conferences which aimed to educate the workforce more broadly about the state of play. Once this had been achieved, management began sharing corporate accounts with the Works Committee and discussing some quite intricate issues of business finance, including how much of profit should be paid as wages and how much paid as dividends to capital. Renold acknowledged frankly that there were disagreements over this issue, and the problem remained unresolved, but it seems clear that the discussions and disagreement took place in an atmosphere of mutual harmony.

As Renold says, ‘there has been a marked convergence of the points of view of management and the workers and a growing tendency to regard the safety and progress of the business as a matter of deep concern to all engaged in it.’ Over time, familiarity has bred harmony, and management and the workers now identify with a common interest. Renold’s account will be of interest to anyone studying works committees or engaged with them in practice.

Bibliography

Urwick, L.F., The Golden Book of Management, London: Newman Neame, 1956.

Witzel, M. ‘Renold, Hans’, in M. Witzel (ed.), Biographical Dictionary of Management, Bristol: Thoemmes Press, 2001.

Original Source

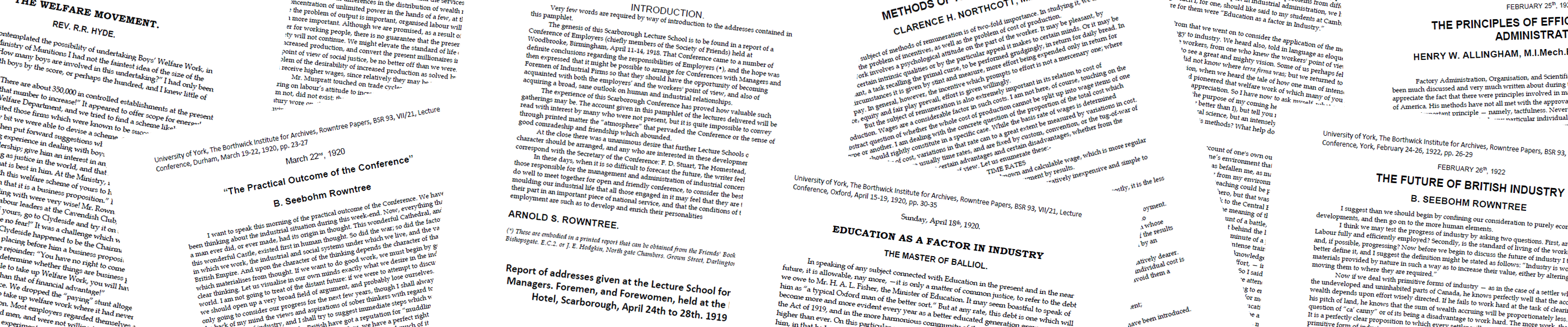

‘The benefit to the workers of scientific management’, 16 April 1920, Balliol College

‘An experiment in publicity of accounts’, 2 October 1925, Balliol College